Chronicles

Sitatara—former caretaker and now a long-term retreatant at the CCR North America—reflects on the unexpected transformation she has experienced so far as a full-time contemplative.

I was tired of being stuck in survival mode—coping, moping, chaotic, neurotic, grasping for ground. After a childhood and young adulthood marked by abuse, followed by a lifetime of complex trauma—including every topsy-turvy way to cope with that trauma—I’d had enough. I couldn’t keep living on that helter-skelter, existential autopilot. I needed to be careful though that retreat wasn’t an excuse to run away from everything I no longer wanted to face. It’s true that sometimes, even here, it’s easy for the mind to slip back into old patterns of escape. Alas, such are the ways of facing one’s own personal samsara while dredging the ooey-gooey, sticky, stinky depths of the psyche—for it’s hard not to rely on one’s habitual ways of coping when squarely confronting all of the things one tucked and shoved neatly and deeply away in order to make it through each day. My habit has been to run away, both physically and figuratively. I’d become adept at not only traveling long distances with my body, but also with my mind. So, what happens when the running away that shadowed me as an endurance adventurer and a full-fledged trauma escapee screeches to a halt—and I stop, breathe, and embark upon an open-ended, solitary meditation retreat? An emerging from the mud, at last.

Upon stepping into my current open-ended retreat, I drew upon many of my survival strategies. My traumatized body and mind were convinced that something awful was about to happen as the familiar intensity of everyday life was replaced with a calm, quiet spaciousness… I had done several one-month retreats in preparation for long-term retreat, but I still found myself somewhat flailing about as I was diving into the mysterious depths of samsara’s ocean. Although this descent is ultimately a solitary pursuit, fortunately none of us have to navigate those depths completely alone nor without proper “equipment”: We have the deep-dive gear of these authentic practices and our “dive guides”—Lama Alan, Yangchen (Eva Natanya), our lineage teachers, and the awakened ones—as well as the support of the wonderful staff, volunteers, and CCR community around the world!

With that support in place, I could now meet what awaited beneath the surface—the grit and grime of my mind, laid bare in the stillness of retreat. But that’s not to say it all evokes reactions akin to Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” painting. That is, I also wouldn’t be discovering a wellspring that I’d only ever tasted drops of prior to retreat. The practices we’re given truly work to strip away all of the filth and fluff that keep us stuck on a perpetual hamster wheel of suffering and sorrow. Sometimes the stripping process can be painful and contracting; other times it can feel like a big release and a deep sigh… I’ve learned the hard way—that is, through a stubborn, habitual holding on—that it all goes much smoother the deeper one can relax. Even the little lessons about how best to support oneself, mentally and physically, in order to cultivate greater ease, can be taken into everyday life. Relaxing has become one of my sharpest, squishiest, softest, most supportive tools. With that foundation, the deeper work can then unfold in a gentle, manageable way.

Upfront, for me, the opportunity for retreat has been one to heal not only complex trauma, but also the deeper, more systemic trauma arising from a mind that’s been sloshing and agitating around in samsara for countless eons. There came a point when I clearly recognized that the very survival skills I had relied upon to navigate challenging circumstances had become a kind of bondage, shackling my ability to heal. The very skills that were once essential to my resilience had now become obstacles to cultivating inner peace and contentment. When I began to make the effort to stop coping through the challenges of retreat, and my mind and body gradually released their reliance on crusty, old survival patterns, an abundance of opportunities began to arise. By taking the daunting yet transformative step of moving beyond habitual coping, one accesses the grandest opportunity available: genuine well-being.

I began to see that the resilience that had carried me through so much adversity could be transmuted into an enthusiastic perseverance to navigate the challenges of retreat. And, in turn, the fortitude gained in retreat undoubtedly will be carried into every day life, but in a much healthier, more sustainable and intentional way—fueled by genuine well-being and the deep desire to want to be of service to all beings, rather than merely the self-centered and instinctual need to survive.

With the mind settling into awareness and intention, another essential thread of the path came alive for me: the profound role of ethics in guiding our choices and actions, both on and off the cushion. As I gradually released my grip on survival mode, I found the capacity to broaden my perspective: I became more aware of my personal values and ethical responsibilities, and developed the awareness and compassion needed to minimize harm in my actions. Further, recognizing that we all seek happiness and are interconnected in our shared existence encourages us to cultivate genuine care for all beings, whether they are our closest friend or a spider on the wall. I found that when my actions are guided by an ethical awareness and intention, then my mind can settle more deeply, fostering genuine well-being and nurturing an active connection to our shared interdependence, which flows forth into compassion and care for others.

A contemplative way of life has also prepared the ground for another practice to take root more firmly: lojong, or mind training. By understanding our ethical responsibility and the ways our well-being is intertwined with others, we create the conditions for lojong to blossom. Whether in daily life or in retreat, every circumstance—pleasant or challenging—can be turned into an opportunity to cultivate wisdom and compassion. In this way, I echo what I’ve heard from many of the teachings: Your current situation is the perfect situation to practice. Maintaining continuity of practice amid any and all of life’s beauty and beasts by using the lojong teachings, turns perceived obstacles into modes of empowering your practice. In Transforming Felicity and Adversity Into the Spiritual Path by the Third Dodrupchen Rinpoche, he writes, “Moreover, by training in actually bringing adversity onto the path, you will encounter unprecedented benefits, for you will see for yourself how adversity can enhance your spiritual practice, and your sense of well-being will continue to increase. It is said: ‘If you practice at first with minor adversity, it will gradually become easy; and in this way you will finally be able to practice even in the face of great adversity.’” This incremental way of training the mind allows us to handle increasingly more challenging situations. So, one need not wait to enter into retreat before practicing. Just stop, look, and listen—what’s happening right now in your life with which you can practice and that will cultivate deeper loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, impartiality, patience, wisdom, and awareness? To take care of oneself in this way is such an act of loving-kindness that, with the right intention, will ultimately benefit all beings.

The deep dive of retreat is not to escape life, but rather to meet it fully—with intention, courage, and care. In observing and releasing our habitual patterns, we discover a steadiness of mind and heart that carries naturally into the world. With each intentional step, the courage and insight forged from this descent rise like a blossom from the mud, carrying their transformative strength into every moment of everyday life—for the benefit of all!

An anonymous retreatant at the CCR North America reflects on why retreat matters—not only to their own well-being, but also for the flourishing of the whole world.

“How wonderful, in this dark and troubled time,

You fortunate ones who wish to practice in retreat!”

—Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche

As one of my Dharma teachers once said, a long-term retreat is not an event—it’s a way of life. Somewhat surprisingly to myself, I’ve recently ventured into my second year of retreat here at Miyo Samten Ling. While reflecting on one’s achievements at what we perceive as calendar milestones might not be the best idea, I found it meaningful to share some of my thoughts and experiences when I was invited to do so.

Specifically, I’ll touch on topics such as the rationale and motivation for long-term retreat, dealing with upheavals and distractions, balancing effort and relaxation (both in formal practice and off the cushion), estimating progress, and living in a contemplative community. Hopefully, this will be of benefit to those considering engaging in such a retreat in the future, or to those who are simply curious about what we’re doing—or, rather, not doing—here.

Why Engage in Long-Term Retreat?

There are plenty of reasons why someone might want to go into retreat: longing for peace of mind, frustration with or inability to cope with life’s circumstances, the intention to become a “better version” of oneself or a spiritual teacher, and even the desire to impress or please one’s own teacher(s). However, not all of these motivations are sustainable in the long term. One has to become completely disillusioned with worldly matters in order to devote oneself single-pointedly to Dharma practice. The four revolutions in outlook are specifically designed to reorient us toward Dharma, but one needs to relate them to one’s own life experience; otherwise, they will remain at the level of mere affirmations.

I’d dare say that authentic practice in retreat—and Dharma practice in general—has little to do with reaching a more comfortable state of mind or becoming a happier person, although these can arise as byproducts of practice. Dharma practice is, first and foremost, concerned with fathoming the true nature of reality and then manifesting it through one’s being in the world. I like how Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche put it: “The bodhisattva vow is the vow to understand the Truth, and then help others to understand the Truth.”

In this respect, long-term retreat is a rare and precious opportunity to prepare one’s mind for such inquiry by means of śamatha, and then engaging in it by means of vipaśyanā, which, when united, lead to genuine inner transformation. Such deep work is only possible in seclusion, where there are minimal distractions and a unique chance to encounter your demons face to face, without covering them up with work, relationships, entertainment, or various addictions. Over time, you begin to see your coping mechanisms more vividly; you start to realize how deeply confused we are as sentient beings—and that the only path to healing lies in fully understanding and transcending one’s delusion.

That said, it’s certainly not the case that one cannot be of benefit to others without first spending a few years in retreat. As Lama Alan pointed out in a recent Wisdom Dharma Chat, “You don’t need śamatha to help other people—you can help them in myriad ways, including teaching basic meditation, yoga, bodhicitta, and so forth. Sometimes your companionship is what people need more than anything else.”

Ideally, one has already developed authentic motivation, renunciation, self-confidence, and all other inner prerequisites before entering long-term retreat. In reality, however, that’s not always the case—at least, I wasn’t so well prepared and didn’t know whether I’d last more than a few months. The good news, though, is that we can continue cultivating these qualities while in retreat. Eventually, if we are persistent enough, Dharma practice will scrape away our superficial preconceptions about what we truly want and how that can be actualized.

Exploring the Inner Landscape

As many of you probably know, intense meditation practice can often catalyze various meditative experiences or upheavals, known in Tibetan as nyam. In fact, as Dr. Eva Natanya stated in her Wisdom Dharma Chat talk, “In retreat, you come to face your personal samsara . . . So we need the courage to persevere through the many layers of ourselves.” Upheavals differ from person to person and can manifest as physical or psychological conditions, or as external events—both pleasant and unpleasant. One thing is certain: you’re going to learn a lot about your own psyche, including the contents of your unconscious mind.

I’ve found that taking the stance of an explorer-observer helps me gain a bit of distance from the mind’s contents and avoid being completely swept up in them. Although at some point we need to lose interest in whatever arises and simply notice it, in my experience this often only becomes possible once I’ve understood what it is that repetitive nyam are trying to “tell” me. In this regard, especially if a specific upheaval or pattern persists over a long period, a psychological consultation might be helpful as a complementary way to figure it out.

Another powerful technique is to apply vipaśyanā by asking oneself, “Who is experiencing this now?”—a question that naturally leads to disentanglement. In his recent Dharma talk available in our Seeds of Wisdom library, Doug Veenhof describes this method, along with other ways in which we can use vipaśyanā to support our śamatha practice.

For beginners like myself, rumination is probably one of the main challenges, apart from upheavals. The egoic mind is remarkably ingenious and cunning—it’s like a YouTube algorithm that knows exactly what to show you to grab your attention. You have to stay constantly vigilant, as it always finds new ways to seduce you into rumination and thus sabotage your practice. But watching the mind’s tricks can be even fascinating at times.

My favorite meditation instruction is extremely simple yet profound: “No distraction, no grasping,” by Lerab Lingpa. Awareness can be as vast as space, and yet grasping arises and collapses it down to the size of a single thought or sensation. In fact, only through intensive practice have I begun to notice how contracted my mind is most of the time. But by simply noticing this again and again, the claws of grasping gradually loosen and give way to spaciousness.

Can You Get Tired of Doing Nothing?

Although awareness itself is effortless, it takes a certain effort to overcome our habitual propensities for mind-wandering and dullness. As Lama Alan remarked in one of his teachings, “You’re not tired of awareness, you’re tired of practicing poorly.” To practice efficiently, one needs to find a very subtle, dynamic balance between effort and relaxation. For me, this hasn’t been easy; sometimes I still veer toward one extreme or the other and end up either exhausted or overindulging in distractions.

The simple technique of first arousing awareness and then releasing it is generally meant to address this problem within a meditation session. It can also be helpful on a larger scale. Once, I experienced a major burnout by exerting myself too much for nearly a month, and it took me weeks to recover from the resistance to practice that followed. I think it is very important to be realistic about how many hours of formal practice one can afford at the moment and not push too hard. Being kind to oneself is crucial, but in my case, it is also important to watch out before this kindness mutates into self-indulgence.

Regarding striking this delicate balance, I resonate deeply with what Dr. Eva Natanya writes in her extremely helpful overview of the CCR’s first five years: “The most important first step is to find contentment with being in retreat—being alone with one’s mind and body, free of major hedonic stimuli, without needing to rely upon conversation or social engagement to stay inspired.”

Of course, subjectively, there can be “good” and “bad” days, but when one finds this general contentment in simply being here and now and practicing Dharma, these fluctuations no longer matter. Continuous practice gradually loosens the grip of attachment to external stimulation, so there is no need to impose radical austerities artificially, although some restrictions on Internet use or socializing can certainly be helpful!

Pulling on Saplings, or On Progress in Retreat

Despite having heard many times that a Dharma practitioner must go beyond all hopes and fears, I’ve found that it’s easier said than done. Each small “milestone” in retreat—three months, half a year, a year—would bring up doubts and a sense of unease about whether I’m progressing enough. Lama Alan compared this tendency to planting tree saplings and then trying to pull them upward so they grow faster, which, of course, is absurd.

It seems that the expectation of rapid progress is what hinders it the most. And, in fact, any expectations at all. The main and only task is simply to return to the practice again and again, without unnecessary commentary or self-reproach. And then one day you notice that something has shifted, something has changed, something has fallen away, something new has appeared.

I think it’s important to cultivate trust in the natural unfolding of things, since the desire to control and the longing for achievements come from our egoic mind, which is, in a way, a product of dualistic grasping. But the desire for quick results—especially at the beginning—is very typical of modern people who have only just pulled themselves out of an endless race for “successful success” and are trying to recover, or rather, return to their true selves. And this process, in most cases, is gradual.

The Perks of Shared Solitude

Before I arrived at our hermitage, I somewhat underestimated the importance of practicing in a community of like-minded people, since I had never had such an experience before. But now I realize that if it weren’t for the kindness and generous support of my teachers and Dharma siblings, I wouldn’t have lasted long in retreat.

Even though most of the time we spend in our isolated cabins on our own, there is a sense of fellowship that sustains us in our individual quests. Occasional interactions can take the form of silent salutations, exchange of written notes or emails, sharing food, or a meaningful conversation once in a while. Besides, there are regular monthly gatherings in our Chapel for teachings and communal practice, which also greatly support our retreat.

I would like to express my deep gratitude and admiration to all my fellow retreatants who were or are currently practicing at MSL or elsewhere; to our incomparable caretakers, thanks to whom all problems are quickly solved and groceries arrive on time; to our wonderful administration for running the hermitage and helping with paperwork; to all the generous supporters donating to the CCR’s Retreatant Support Fund, which allows some of us to continue our retreats; to our Research and Education Director for her extraordinary warmth and support; to all the volunteers who help with multiple tasks; and to the CCR’s benefactors and friends, without whom all this would not be possible. First and foremost, I am forever grateful to Lama Alan and my other Dharma teachers, who with great patience and compassion guide sentient beings toward awakening.

Sarva Mangalam!

Natalia Bojanic reflects on the awakening effects of retreat and finding the balance between meditation practice and the responsibilities of daily life.

Returning to Home

Ironically, I am writing these words not from a place of stillness but in the midst of London’s bustle, with a restless mind that longs for the vast, open land of Crestone. The memory of Miyo Samten Ling (MSL), where I was blessed to spend two retreats, ten days in August 2024 and twelve in April 2025, reminds me of what it feels like to live with few concerns, wholly dedicated to Dharma.

Revisiting my retreats brings a mix of gratitude and, I’ll admit, a twinge of heartbreak. Gratitude for the gift of silence, simplicity, and solitude. Heartbreak because those days are so strikingly different from my reality of juggling two careers, a Master’s degree, a relationship, a teenage stepdaughter, family in Brazil, and all the movement of a modern city.

What surprised me most in both retreats was this: I didn’t miss my busy routine. Not one bit. The silence felt like home. The solitude was nourishing, and I found authentic joy in the smallest encounters: the deer grazing nearby, the song of the birds, the presence of a rabbit, or even a tiny spider. Maybe that’s an indication I did miss humans a little!

The Gift of Spiritual Community

Though silence was the cornerstone of the retreat, a few interactions with others (via notes, emails, or brief encounters) were a balm for the heart. I remain deeply grateful to caretakers Sitatara and Aaron, who cared for yogis with such genuine kindness that I felt more looked after in the Colorado mountains than anywhere else in the world. I am honored to call them my Dharma sister and brother.

I am also deeply grateful to Eva Natanya, who welcomed me so lovingly and made these retreats possible. Eva’s generosity opened the door for what felt like quantum leaps in understanding. Concepts clicked, meditations deepened, and suddenly the Dharma felt less like an abstract ideal and more like an embodied possibility.

Trying to Explain the Unexplainable

When non-Dharma friends ask me, “But why silence? Why solitude?” I try to explain that retreat connects me with something far beyond this body and mind. It reawakens the heart, sharpens clarity, and nurtures a sense of belonging not just to people, but to the environment at large. The blessings of conducive circumstances gently and gradually dissolve the boundaries between oneself and everything else. Even as the memory fades, I try to return to it often for perspective and wonder, like revisiting a favourite song that never really leaves you.

Lama Alan’s Prescription for Integration

When it was time to return to the “real world,” I felt sadness to leave MSL and fear of losing what is most precious, so I asked Lama Alan for his advice on integration. He warmly offered two practical jewels:

- Four Immeasurables: orient the mind towards kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity in all circumstances. I find that especially helpful when using public transport in rush hour!

- Spiritual Friends: keep good company. The Sangha sustains the teachings when busyness distracts. I feel lucky to have wonderful Dharma friends around me.

Simple and completely doable, no mountain required.

Building Toward Long-Term Retreat

My short retreats have inspired me to prepare for longer ones. Though the time is not yet ripe, I have set a timeline and a clear intention. Until then, I continue to build momentum through half-day retreats in London, week-long retreats in the UK countryside, and, most importantly, through the simple daily rhythm of practice at home. Just because the possibility of a long retreat is not here now does not mean preparation should wait.

And so, my Dharma friends, I leave you with this encouragement: don’t wait for “perfect” circumstances. Do what you can, where you are. Stillness can begin in the mountains, or in the messy miracle of our daily life.

Retreat is not only a place but a way of returning, again and again, to what is most real and true.

May we all find moments of silence amidst the noise and stillness in busyness.

The CCR's “Pilot Study” yields its first peer-reviewed research article, available to read for free in Frontiers in Psychology

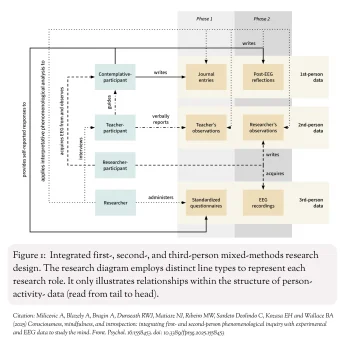

Since 2020, the CCR’s Research Team has been conducting a mixed-methods study on the phenomenology of shamatha- and vipashyana-based meditation retreats for full-time contemplatives-in-training. Concisely referred to as the CCR’s “Pilot Study” and led by Principal Investigator Dr. Anita Milicevic, this flagship project combines the expertise of researchers across three continents. Now, after five years of planning, data collection, and analysis, the CCR is delighted to announce the first of multiple research articles expected from this project: a methodology paper titled “Consciousness, mindfulness, and introspection: integrating first- and second-person phenomenological inquiry with experimental and EEG data to study the mind,” now available in the journal Frontiers in Psychology.

As the authors discuss in the paper, the Pilot Study operationalizes a core strategy of our contemplative-scientific research program: combining first-, second-, and third-person data to maximally triangulate perspectives on the mind. The study seeks convergence across these methods so that each can illuminate what the others cannot—and, where needed, compensate for potential biases in the other methods. (Those seeking to learn more about the epistemological justification for this approach may be interested in a recent book chapter on the subject by B. Alan Wallace and Nicholas J. Matiasz; a full preview is available here.)

For instance, contemplatives-in-training who are enrolled in the study write journal entries about their meditation practices. This first-person data conveys nuances about subjective experience in a way that third-person measures like psychological questionnaires and EEG simply do not. But as many people who have meditated can attest, it can be easy to be mistaken about one’s own progress. While the meditation teachers guiding the contemplatives-in-training do not read the first-person research journal entries, they offer second-person data, by reporting their perspectives on participant progress.

Lastly, EEG provides evidence about brain activity that may be correlated with mental processes occurring during meditation—a form of third-person physical evidence that does not share the same susceptibilities to bias seen in first- and second-person reporting. The power of this mixed-methods approach lies not in merely collecting multiple forms of evidence but in integrating them. Of course, these disparate data streams cannot be combined as simply as adding three numbers (e.g., 3 + 2 + 1 = 6); more elaborate integration procedures are needed. Part of the CCR’s research program—and part of the aim of this new paper—is to articulate procedures for integrating diverse forms of first-, second-, and third-person evidence on the nature and potentials of consciousness. Through such integration procedures, synthesized knowledge can be derived from these data streams—knowledge that cannot typically be obtained from simply analyzing the data streams in isolation.

The authors argue that this mixed-methods research has been underused in studies involving meditators. For the growing field known as contemplative science, the lesson is practical: careful first- and second-person data—although rooted in subjectivity—can strengthen the scientific method by yielding phenomenological descriptions that help interpret psychological and neuropsychological findings. The goal is not to achieve objectivity by rejecting the subjective, but to recognize that objectivity is achieved only via intersubjective agreement, through honing the mind so that expert consensus can be reached and then further corroborated by third-person means.

In response to this need, the study applied Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), to bridge contemplative science and Western psychology, and to integrate first-, second-, and third-person data, creating new forms of knowledge. This paper thus gives the CCR’s research program a clear, citable template for seeking this form of convergence, while highlighting a gap in the theoretical and methodological thinking behind this type of research. That is, most meditation studies still don’t treat contemplatives as true researchers of the mind. The CCR’s Mind Lab and Research domains are designed precisely to address this gap.

Dr. Eva Natanya reflects on our first five years as a true "Center for Contemplative Research," as well as the beauty and difficulties of long-term mind training in solitude.

We have an intrepid mission at the core of our work at the CCR, to create conducive conditions for dedicated practitioners to train their minds in rigorous, long-term retreat, with the aspiration to cultivate sublime levels of mental balance and compassion, and to gain transformative insights into the nature of reality.

But if you’ve read Benjamin’s beautiful account in our last Chronicle, you might have gathered by now that the typical day-to-day experience of long-term retreat is not always characterized by blissful meditations and profound discoveries. Indeed, many retreatants report going through some of the most challenging experiences of their lives—emotionally, physically, and spiritually. But why?

Nyam—Meditative Experiences in Retreat

As prospective retreatants prepare for their yearned-for solitude and silence—with nothing else to do all day but practice Dharma—they learn about something the Tibetan Buddhist tradition has termed nyam. This can be roughly translated as “structured experiences,” or more specifically “meditative experiences.” It is not as though all these experiences happen while formally meditating, however. Rather, these include a wide range of physical, mental, and emotional experiences that arise as a result of a correct practice of meditation, and which can happen either during meditation or anytime between sessions.

These experiences are a by-product of the crucial process of dredging and purifying the many layers of the mind, which naturally involves uncovering buried traumas, insecurities, habitual attitudes, misconceptions, memories of one’s own positive and negative actions, and at a very raw level, tasting what it feels like to grasp to “me.” That is, we begin to recognize the root of our suffering in the experience of holding onto a prelinguistic construct of “me” that is actually unfounded in reality. But it can be quite a shock to discover that the “me” I thought was there doesn’t exist in the way that I thought, and never has. And sometimes the mind and body temporarily rebound into grasping more tightly than before.

Perhaps needless to say, such experiences are not always fun. Yet, if one is properly trained in how to remain grounded in the stillness of awareness and observe these experiences without following one’s ingrained habit of grasping to them or identifying with them as really being “mine,” they can naturally release themselves. Because the experiences are being catalyzed from within the depths of one’s psyche, and are naturally impermanent, if one ceases to fuel them with grasping and fretting, they will eventually exhaust themselves and disappear.

It takes an enormous amount of confidence in one’s teachers and the path that has been explained by countless contemplatives of the past for one to have the courage to endure such experiences while they are occurring. But as one continues in the practice of meditation, dwelling in the stillness of awareness as mental processes arise and cease of their own accord, there is a deep and quiet reward in knowing that the mind is being purified from within. One gains the confidence of being able to face one’s innermost demons and not be conquered by them.

The profound purification catalyzed by meditation may surface not only at the psychological level but also at the physical level, leading to strange and sometimes disturbing experiences of energies coursing or jolting through one’s body. This release of subtle energies (or prana) within the body can sometimes revive pain from old injuries, create new physical pains, or even trigger both diagnosable illnesses and undiagnosable issues. But it can also gradually heal deep-seated residues of trauma.

Even more surprisingly, the purification process that is brought about through one’s authentic practice of meditation in retreat can catalyze what are known as “outer upheavals,” or events in one’s external life and environment that are all too real, and that can indeed threaten to distract from or hinder one’s ability to remain in the silent retreat to which one is committed.

A practitioner must then discern very carefully to see what situation, without doubt, needs one’s attention through loving and compassionate action, and what distraction may simply be a temptation to abandon retreat practice, yet without one’s actually being able to benefit the outer situation by leaving retreat, either.

Navigating Serious Psychological Upheavals

Frankly, one needs to be quite psychologically healthy and balanced even before entering retreat in order to have the capacity to sustain retreat practice joyfully and successfully amid such an array of unpredictable meditative experiences, which arise differently for every person. The CCR’s Sixfold Matrix of Mental Balance is being developed as a training program that can guide practitioners in assessing and enhancing their own mental balance, whether they choose to remain engaged in the world or are preparing for solitary retreat. At a physical level, some practitioners may also benefit from time-tested, professionally guided methods of somatic trauma release before engaging in extended periods of solitude.

Yet sometimes individuals discover the depths of hidden psychological imbalances only once in retreat—even years into a retreat. Since our inception as a mind lab/hermitage, we have always had a team of experienced psychologists available for confidential consultation with any retreatant, whether by video call or in person. Different levels of care are offered depending on someone’s situation, and if a deep crisis arises, psychologists are ready to offer close care as needed. This remains private to the individual retreatant, and fellow solitary retreatants would usually not know and do not need to know when psychological care is being provided for a fellow retreatant. At such times, however, it is crucial for retreatants to consult with their spiritual teachers to discern whether it may be the right time to depart from retreat in order to recalibrate and seek healing through sustained professional assistance, as well as through regular contact with supportive friends and family. Indeed, there are times when the nature of an issue that has arisen is so acute that it is not healthy for a person to remain in solitude, and in such cases we, as spiritual teachers, have encouraged such a person to depart from retreat.

In other cases, certain individuals can discern that they have the capacity to continue full-time retreat practice straight through the particular psychological or physical upheaval, and see that they will find deeper healing right there within retreat than they might ever be able to do out in the world. This path of manifest healing has occurred numerous times for retreatants at the CCR and is a source of great joy for all of us. More details on the theory behind meditative experiences and how practicing with them properly can enable one to proceed further along the path of meditation will be the subject of a future Chronicle. Suffice it to say, one needs a profound view of reality to be able to release such intense experiences without grasping to them as if they really exist in the way that they appear.

Understanding Different Models of Retreat Life

Since our first group of retreatants began long-term retreat at the newly-founded Center for Contemplative Research in November 2020, we have certainly learned a great deal about the enormous variety of meditative experiences—both difficult and very beautiful—that can occur for different individuals.

As Dr. B. Alan Wallace has emphasized many times, we are breaking new ground in our efforts to establish a retreat center in the West where the focus is explicitly on creating the conducive conditions for retreatants to practice single-pointed meditation with the aspiration of entering the Mahayana Path. This means that we practice in sustained solitude and silence with the aspiration to develop sufficient stability of mind and openness of heart to bring about lasting and irreversible change in our own being, to embody the compassionate motivation to be of highest service to all sentient beings.

There are of course retreat centers around the world, many based in different spiritual traditions, which are focused on similar overall goals. But the model of long-term, solitary practice that we emphasize at the CCR is admittedly more rigorous than at most retreat centers or even monasteries in the East or West.

Most Christian monastic or lay intentional communities gather regularly (daily or weekly) in service and liturgy to reaffirm the communal aspect of individuals’ commitment to a certain vision and form of spiritual practice. Within the Buddhist tradition, especially as established in the West, rituals and meditations practiced as a community are a regular part of even the strictest of retreat periods. Think of your typical image of a Zen monastery or a Tibetan three-year retreat, where formal group practice is an integral part of the discipline.

Our CCR Mind Lab in Colorado is in part modelled on a different style of retreat, one which has been common in Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal, and India, but which has fewer precedents in the West. This is a model in which a group of individual retreatants would be spread out across a mountainside or valley, each in their own small dwellings, each under the guidance of their own teacher, keeping to their solitary practice for months or years at a time. There would be a loose-knit association among these practitioners, such that they would know if someone was ill or needed emergency assistance, but they would never meet together for group rituals or communal practice. All practice is performed in solitude within their individual huts. In Christian monastic history, this would be closer to the eremetic desert tradition, as distinct from the cenobitic monastic tradition.

What We’ve Observed and How We’ve Adjusted

In our first few years as a CCR, we tried our best to follow this solitary retreat model closely, as it has proven for centuries to be the most conducive model for attaining states of meditative stability such as shamatha, as well as deeper insights into the nature of reality. We discovered over time, however, that while such solitude and silence certainly enabled retreatants to delve deeply into their meditative practice, long-term retreatants were not always able to weather the enormity of the meditative experiences catalyzed without more regular, structured community interaction and ongoing teachings from their spiritual mentors.

We also gradually recognized that while retreatants all had a good deal of training in core practices prior to entering retreat at the CCR, many had not yet been sufficiently prepared to sustain the level of strict retreat to which they originally aspired (e.g., 8–12 hours a day of meditation). That is, some retreatants dove in with gusto and could maintain this intensity of practice for weeks or even a few months at a time, but then would find themselves overwhelmed by a particular meditative experience or upheaval (as described above), which would inevitably break the continuity of their meditation. If, over many cycles of effort and interruption, the disturbing experience lingered without releasing, then remaining in silent solitude would sometimes seem like an oppressive prison sentence rather than the liberative retreat they had been seeking.

The Importance of Maintaining Continuous Practice Through Silence

Sometimes, however, the urge to interact socially seemed to fall to another extreme, with conversations among retreatants burgeoning for hours upon a chance meeting in the community building or along the hermitage roads. There were times when we, as spiritual guides, needed to experiment by expressing clearer guidelines around maintaining silence in community spaces, so as to preserve the atmosphere and safety of silence for other retreatants who were still in the flow of their practice and would not want to be drawn into long conversations. Trips away from the hermitage for medical appointments are on occasion necessary for retreatants, and our retreat boundaries are not so strict as to prevent this. Nevertheless, at times we asked retreatants not to engage in conversation during the long drive with one of our caretakers, and also not to extend the trip with personal grocery shopping or a meal at a restaurant, which we all know so well can disrupt the single-pointed flow of long-term retreat (in which, traditionally, one would not go into a town at all). Rather, since our retreat caretakers, or stewards, are already responsible for obtaining groceries for retreatants on a weekly basis, retreatants should not have the need to go into public places separately. Such temporary rules were intended to help retreatants settle into a more habitual mode of silence and sustained practice, but we also saw that when some retreatants seemed to struggle with such guidelines, it was because something deeper was not yet balanced in their overall life of retreat. We recognized that these were times to encourage retreatants to delve more deeply into the overarching motivation for retreat, cultivating a heart-rending compassion for the suffering of all beings and an understanding of how the discipline of retreat—which includes refraining from distractions—can be in direct service of the much larger goal of cultivating irreversible transformation of one’s mind and habituations.

More recently, we have not even found it necessary to emphasize such guidelines on physical and verbal retreat boundaries, because, as our hermitage community matures at many levels, we have found that retreatants more naturally maintain silence as a matter of course. Current retreatants are inclined to greet one another in total silence, expressing a respectful gesture of warm-hearted kindness and admiration without needing to engage in conversation. Moreover, we have seen that open conversation among retreatants on the day of our now-regular (monthly) gatherings can then be welcomed as healthy and refreshing, since it does not then become a persistent mode of distraction from the main work of retreat.

Reporting to Teachers on One’s Practice

We have also experimented with different rhythms for retreatants’ reports on their meditation practice. At the end of 2020, Dr. Wallace developed a set of eight questions by which he asked all CCR retreatants to report regularly, via email, on their practice. These eight questions cover topics from the hours each day devoted to shamatha and other supporting meditations, inquiring about how meaningful each of these practices is for the retreatant, about challenges one has been facing and how one has dealt with them, about meditative experiences (nyam) and insights that may be arising, about how one is maintaining balance in practice both during formal sessions and between sessions, about how one is maintaining overall health in terms of diet and exercise, and about how one is finding satisfaction in the practice.

For most of the first two years of our existence as a hermitage, Dr. Wallace was providing guidance from afar, both through monthly video calls with our community and through private email exchanges in response to retreatants’ monthly written reports, as prompted by the eight questions. Doug Veenhof and I were present on-site for meetings when requested by individual retreatants, and occasionally I would hold scheduled check-ins with each retreatant. Individual meetings with Lama Alan were rare, occurring only when he would visit to lead one-week or eight-week retreats.

At the beginning of 2023, Dr. Wallace (also known as Lama Alan) entered his own long-awaited personal retreat in Crestone, and urged all retreatants to enter that deep silence with him. For six months, he no longer asked for monthly written reports, but invited retreatants to write to him only if they discerned that it was really necessary, that is, if they had an urgent issue for which they sought personal guidance. By the end of those first six months of 2023, however, Lama Alan and I were deeply saddened to discover that most retreatants had struggled through that period of strict retreat, which had included one in-person meeting with Lama Alan for each of them midway. We realized in retrospect that the majority had not reached out, even when issues had actually arisen in their retreats that should have received our attention. We saw from our experiment in strict silence that at that juncture, even experienced retreatants were not yet ready to remain in a flow of completely uninterrupted retreat for six months. So we again decided to require written reports—now submitted every other month—as the standard for all retreatants’ regular communication with Lama Alan, our spiritual director.

Community Gatherings, Ongoing Teachings, and Individual Meetings

From mid-2023, we also continued to experiment with different cadences for our community gatherings and teachings. We met for group rituals and teachings from Lama Alan in August and October, and then, beginning in November 2023, Lama Alan began offering public teachings roughly every six weeks, which we gradually made available to our larger local community and also online here.

From the beginning of 2025, we established a monthly rhythm that has seemed to work as our most conducive cadence for retreatants thus far. We now alternate monthly between a short teaching followed by a community ritual practice, and a longer teaching geared toward experienced retreatants. Collectively, these are the teachings we now make available to the public through the Seeds of Wisdom Library.

We have clarified for all retreatants that they are welcome to reach out to Lama Alan with a practice question between bimonthly reports, and we are finding that retreatants do so when appropriate. Lama Alan is of course willing to break his own retreat silence to hold an individual meeting with a retreatant when a clear need arises, though such occasions are relatively rare. Retreatants also reach out to resident teacher Doug Veenhof or to me to discuss particular issues in their practice, whether by email, phone, or in person.

Overall, meetings are held on an individual, as-needed basis, and not as a regularly scheduled part of retreat life, which helps to preserve the flow of silence for all of us at the hermitage between monthly community gatherings. When they occur, one-on-one meetings with a spiritual teacher can range in length from 30 minutes to 2 or 3 hours.

While we as teachers cannot magically make the internal process of purifying the mind and body through intensive meditation practice easy, we do sense that we have found more sustainable ways to help practitioners through these difficult and highly rewarding experiences of transformation.

As explained below, we have also modified the way that we guide retreatants into retreat in the first place, which has had a noticeably beneficial effect in the many short- and long-term retreats that were begun throughout the past year.

A Progressive Model of Retreat Structure: Level-One, Level-Two, and Level-Three Retreat

There are numerous authoritative Buddhist texts that state one can ideally achieve the state of shamatha—a transformative level of meditative stability—within six or nine months of continuous practice in retreat. But what is not always clear is how far along the path of spiritual maturity and transformation one needs to have come already in order for such a period of unbroken meditation to be successful.

That is, how many years might one have needed to prepare the mind and body through well-rounded, full-time spiritual practice in solitude and in community before one is ready to embark upon a particular six- or nine-month period of retreat and then continue meditating in an uninterrupted retreat schedule for that entire period, in order for shamatha to come to fruition in one’s mind and body? How can one prepare so as not to encounter such intense upheavals that one is actually derailed from the continuity of meditation again and again?

We discovered within the initial years of the CCR’s existence that we needed to dispel the idea that one could come straight from twenty-first-century life into a six- or nine-month intensive shamatha retreat with the expectation that one could sustain 10- to 12-hour days of meditation right from the first few weeks onwards for six months and, just like that, achieve shamatha and then return to one’s previous life and relationships!

Given the unprecedented stress and ubiquitous wounds of the digital and technological age in which each of us grew up, it is simply not realistic to think we can start retreat with the ideal schedule of a full-on “shamatha retreat” aimed to achieve unwavering stability within six or nine months.

From the beginning of 2024, inspired by detailed shamatha teachings given by Drupön Lama Karma, Lama Alan began formulating the concept of a level-one, level-two, and level-three retreat.

A level-one retreat is structured in such a way that someone transitioning from a socially engaged way of life can come to take joy in practicing Dharma all day long in solitude: gently removed from the sensory stimulation of modern life, one thoroughly immerses oneself in a balanced array of practices to open the heart and mind, settle the attention, and calibrate one’s body and mind to a relaxed and joyful way of being in retreat. One might still be listening to recorded teachings each day, taking long walks, and including mantra or other sacred recitations in one’s practice, while still maintaining overall silence as a way of life in retreat. Sustained for a few months, such a schedule will introduce individuals gently to the experience of being in retreat, while still creating the conditions for meaningful transformation and sometimes life-changing insights to occur.

A level-two retreat builds on some weeks or months of such balanced experience and begins to streamline conceptual practices, placing a progressively greater emphasis on silent, nonconceptual shamatha meditation, with less time spent reading instructional books or listening to teachings. How long one spends in this type of retreat will vary from one person to another, but the 6 to 8 hours that one typically spends practicing shamatha each day within such a level-two retreat will be enough to catalyze both pleasant and unpleasant meditative experiences and upheavals, so that one begins to learn how to handle and progress through such experiences wisely and fearlessly.

By the time one is ready for a level-three retreat, one is now so thoroughly flourishing in one’s overall practice that one might feel one is already coming around the home stretch toward sublime balance of body and mind, both in meditation and between sessions. This is the time to begin a six- or nine-month period in which all the outer and inner conditions are in place to meditate 12 to 14 hours a day, every day, continuously.

But again, if one starts this type of schedule too soon, one will get too tight, push too hard, and eventually burn out. One might even keep going at such a pace for a while, but without sufficient preparation in comprehending and embodying the depths and breadths of the entire spiritual Path—within which shamatha is only one practice along the way—one might become bored with a hollowed-out version of the practice. If such a stagnating meditation practice has at some level lost its tenderness of heart and profound inspiration, one might begin to find it pointless in the face of the magnitude of the problems in our world, and eventually give up. So, sufficient preparation for a level-three shamatha retreat is indispensable, to say the least!

Lama Alan has developed this flexible structure of outlining different levels of retreat not as a grading system, but as a reasonable and user-friendly way to help people who have lived in our contemporary age to so thoroughly adjust to what it means to be in retreat that over time it no longer feels like something drastic or intense.

The most important first step is to find contentment with being in retreat—being alone with one’s mind and body, free of major hedonic stimuli, without needing to rely upon conversation or social engagement to keep one inspired. This itself is not always easy, but we rejoice in the many retreatants in whom we have seen this transition take place over the first few months in retreat. That is the first step on a path to true flourishing.

Never Lose Heart—And Don’t Think Small

At the CCR, we see ourselves as pioneers, as explorers. So, learning from our collective experience and, with hindsight, our mistakes, is part of the process. We are taking unprecedented steps in the creation of a contemplative culture in the West. But that means we don’t have ready-made roadmaps for everything we are doing. The breadths and depths of our compassionate motivation are something in which we can be confident, and we also continuously recognize that none of us is infallible. We are a work in progress and cannot simply follow in the tracks of others—even within the Tibetan Buddhist tradition—for we are facing unprecedented situations in the twenty-first century.

We know that we still have much to learn in helping retreatants navigate the effects of previous complex trauma and grief that emerge while in retreat, especially as these manifest deeply within the body and its subtle energy systems.

We know that life in retreat takes an enormous amount of dedication and that it is not for everyone. We also recognize—now that we have been in existence as a working CCR hermitage for our first five years—that incoming retreatants have a much better idea of what to expect and what not to expect from long-term retreat.

They know that it will not be easy, and that no one should get their hopes up for achieving shamatha within six to nine months, if that is counted from the beginning of entering a life of retreat in this day and age. Current retreatants understand that they will not be having regular in-person interviews with resident spiritual teachers, especially when those spiritual teachers are also immersed in full-time retreat themselves.

Incoming retreatants can trust that our marvelous caretaking team will be there to attend to their immediate needs and medical emergencies, and that our global team of psychologists will be available for both interim and sustained help if needed. And retreatants are aware that sometimes such enormous obstacles arise in the course of full-time practice—and life—that it might become necessary to leave retreat, whether to seek ongoing medical or professional assistance for a chronic personal issue, to care for a sick family member, to return to a committed relationship, and so on.

I wish to express my personal gratitude to our spectacular team of staff and volunteers, who have step-by-step streamlined systems that we had to put in place so swiftly and often in ad hoc ways within the first two years of retreat here at Miyo Samten Ling. Our hermitage caretaking system is so smooth now—thanks especially to Virginia Craft, Aaron Taylor, and Jon Mitchell—and this brings much reassurance to my own heart.

For readers who wish to understand more about the traditional relationship with the spiritual teacher, and how one can become closer to that mentor precisely through practicing what he or she has taught, I would encourage you to listen to the recent (August 2025) talk that I offered at our hermitage, “Calling the Guru from Afar,” which is available through the Seeds of Wisdom Library. It is crucial to understand that within our particular model of long-term retreat and hermitage life, one should not enter with any expectation of becoming close to the spiritual teacher through frequent conversations or personal interaction. Rather, in our model, oral instruction is offered primarily to our community as a group, and personal guidance from Lama Alan is done primarily through written correspondence. And the deepest form of relationship with the ultimate spiritual teacher occurs through practice itself, as the many great contemplative traditions of the world have taught. This was highlighted recently by Fr. Eric Haarer in his exquisite talk on “Forgotten Gems of Christian Mysticism.”

We are also delighted to announce the publication of two new books that will serve as textbooks, as it were, for our Center for Contemplative Research. These are Śamatha and Vipaśyanā: An Anthology of Pith Instructions, composed and translated by B. Alan Wallace and myself, and The Vital Essence of Dzogchen: A Commentary on Düdjom Rinpoché’s Advice for a Mountain Retreat, by B. Alan Wallace.

A natural prelude to the latter book was published last year, under the title of Dzokchen: A Commentary on Düdjom Rinpoché’s Illumination of Primordial Wisdom. The root texts and pith instructions contained in these three books are designed precisely for the kind of retreats taking place at the CCR, and readers can learn much about what we practice—at its depths—by studying these books and also the linked oral commentaries included in Śamatha and Vipaśyanā.

Careful readers will glimpse the variety of approaches to the practices of shamatha and vipashyana that appear across different lineages of Buddhist teaching, all of which have been validated through centuries of contemplative experience. The modern commentaries included in these books are intended to help readers navigate these apparent differences, and eventually to reach a sophisticated understanding that can be tested in one’s own dedicated practice.

For all the difficulties that long-term meditation retreat can entail, the vision of a contemplative path to irreversible transformation and the compassionate intentions that inspire such sustained practice eventually make the difficulties pale in comparison. But one needs to understand the nature of reality at subtler and subtler levels to actually see why such practice is so worthwhile from hour to hour, day to day.

If you feel drawn by such a challenging path, we invite you to read more about short- and long-term retreats at the CCR here. While all our cabins are currently booked for most of 2026, and long-term applications for retreats beginning in 2027 are already being considered, we always welcome new applications. There are many conditions that need to come together for a retreat to take place successfully, and the longer in advance one can prepare, the smoother and more meaningful the retreat can be.

Long-term retreatant Benjamin shares the turbulence, lows, and highs over nearly a year in retreat, and reflects on how training the mind can truly benefit of all beings.

Note: This article is excerpted from a longer thank-you letter that Benjamin sent to his close friends, family, and benefactors. He has allowed us to share portions of the piece in gratitude for the support of the greater CCR community. If you’d like to support retreatants like Benjamin directly, consider donating to our Retreatant Support Fund.

Dear Friends,

As I somewhat expected before entering Miyo Samten Ling hermitage, it is indeed difficult to find words to describe what long-term retreat is like and what it does to the soul. In the West we tend to psychologize everything, which hinders the reader’s ability to actually get a taste of what the storyteller wants to express. With these words, I do my best to welcome you to a delicate telling and listening.

Retreat is a bit like being in an airplane with the windows closed. Though changes can be felt here and there along the way, one has little ability to tell just how high and far one has traveled. But there are moments of sensed depth and breadth, both pleasant and disturbing, that give me a hint: “I ain’t in Kansas anymore.”

Turbulence at Takeoff

After a surprisingly painful first few weeks, I started to settle in. Letting go of what is familiar and the warmth of beloved people in daily life felt like a small death. The high, dry desert environment and my settling adrenals kicked my ass. But after a while, I started to feel at home in my retreat cabin, with my body acclimated and my mind settled enough to appreciate long stretches of silence and solitude. Being alone for so long brings me closer to my basic needs—that is, our basic vulnerabilities, ever hinting at the fragility of life. I cherish ever more simple acts of generosity. Enjoying life can be so simple.

My abode is isolated by sight from the others that are scattered about the landscape that surrounds the beautiful, homey community center and chapel where one comes to catch internet reception, pick up parcels, or come together for a common practice once every several weeks. Deer pass by my windows every other day, and the sound of coyotes frequents the night.

I’ve done retreats alone, shorter of course, and I can say it really makes a difference being amid other committed practitioners, some of whom have been here for years. Though we rarely see each other, there is a silent intimacy among us. Though I’m still crawling in my diapers, my daily practice continues to develop and deepen, like a slowly growing garden. The ancient Sanskrit word for meditation/contemplation is bhavana, which means “cultivation.” At the moment, I “cultivate” in formal practice around eight hours a day, and that’s gradually growing. Ambition, pushing, and overthinking don’t work, so it’s a delicate and often difficult task to listen very closely. The time in between sessions also has its special qualities and particular demands. The tenderness and insights that arise now and again remind me that I’m not on an efficient assembly line, but a lively river. So, I can say that on some days, I am in full-time practice from the moment I wake up to the moment I go to bed.

So, what is it that I am actually doing every day?

Settling the Mind in its Natural State

I’ve put myself into a ten-month shamatha retreat, which means the vast majority of my time in formal practice and the intermediate moments are devoted to the cultivation of shamatha, with one to two hours a day of auxiliary practices.

Shamatha is a Sanskrit word (zhiné in Tibetan) meaning quiescence, stillness, calm abiding. It refers to a specific set of practices that develop attentional intelligence. It’s about intentionally developing the ability to maintain a continuous stream of cognizant, focused, relaxed, and vividly aware attention to dissolve the mind’s rampant flip-flopping between dullness and disturbing excitation. In Buddhist training, shamatha is an indispensable foundation for more advanced practices.

One can cultivate a regular shamatha practice with 20–60 minute sessions once or twice a day, as I have on and off over the past twenty years. These types of meditation have been demonstrated to increase mental and physical health, which I can attest to personally. However, with sustained long-term training, shamatha practice takes on a whole new dimension. Essentially, one is settling the mind into its natural ground state, free of coarse and subtle disturbances, idle chatter, and obsessive ideation. It has been confirmed again and again by professional contemplatives over thousands of years: the natural ground state of the individual mind is 1) blissful, 2) luminous, and 3) peacefully non-conceptual. These three salient qualities of the distilled individual mind, along with an unprecedented sense of well-being that emerges, are inseparable from such a refined and developed attention.

But boy oh boy, it ain’t an easy path. All sorts of things can occur along the way—the good, the blissful, the bad, and the real ugly. As one relaxes the body and mind deeper and deeper in long-term practice, the mind dishes out all sorts of things as it purges and heals itself. This phenomenon is referred to as “meditative experiences” (nyam in Tibetan), which can be both pleasant and unpleasant. Like dredging a swamp, as one digs ever so gently but discerningly deeper into the mind, one may come across wonderful treasures: moments of joy, unprecedented clarity, an impenetrable sense of lightness, or perhaps spikes or long arcs of bliss. On the other hand, one may hit sleeping dragons that don’t like being woken up: unpleasant memories, old repressed material, energetic blockages, strange pains in the body, debilitating low self-esteem and confusion, deep-rooted traumas, and all the stuff we shamefully hide from the world. Whatever comes up, the guideline is: don’t take it too seriously, don’t reify, don’t get attached, don’t appropriate—just let it all arise and pass.

Easier said than done. Meditative experiences manifest uniquely to each individual, as we each have our own mental-physical matrices that unravel their blockages in unique ways, and there is no predicting what will come and hit you from the side. In order to discern how best to deal with these experiences, it’s essential to have seasoned practitioners close by, as well as mentors who have traversed their own wonderful and treacherous inner landscapes enough that they can help others navigate their own—as I so fortunately do here.

At the onset of this retreat, my mind’s chatter went wild. It felt like meditation was making my mind more chaotic, not less. Apparently this happens to pretty much everyone who starts to engage in long-term practice. It’s not that my mind was getting more disturbed than normal, but rather I was peeling back the surface layer of my awareness and dipping into the undercurrents that were already there and are always moving below my ordinary state of mind. No way can my mind be this chaotic! A humbling experience to say the least.

All sorts of strange and interesting characters suddenly appear and pass through the space of the mind. It sometimes seems as if they are not part of me at all. Some guests show up frequently over days or even weeks, as if one were watching a television program that one cannot simply turn off. Some examples from my first months included: imagining what possessions I need to downsize in a year in order to pack before I leave Colorado, endless arguments with a particular person, and Thor, the god of thunder. I know that it doesn’t really matter what the content of the thoughts are. If I’m in a state prone to appropriating the movements and contents the mind produces, then pretty much anything will be appropriated. If I am not able to abide in discerning awareness, thoughts, emotions and stories will kidnap and take me for a ride again and again and again and again.

It is indeed possible to rest in the stillness of awareness—something that is always present with us, having the two qualities of luminosity and cognizance—and still have a flood of thoughts occurring in the space of the mind. It’s fascinating to rest in the stillness of awareness in the midst of so much inner movement, where a sense of peace doesn’t entail the mind being devoid of thoughts, and where there is a spaciousness that allows for more patience and humor.

These are the non-threatening kinds of movements of the mind. I’m sure we all know the hellish states of mind that can abduct and torture us, even when not engaging in long-term practice. I’m told that in retreat, one is to treat those states with just as much impartiality as the extremely enjoyable ones. Again, not easy. We need to have great compassion for ourselves.

The Reality of Death

Every morning, whether or not the sun has yet arisen, I contemplate the reality of impermanence and death. What does that look like? To start, I remind myself of the ever-changing nature of life.

One object of meditation I’ve frequented lately is my thinning hairline. Is the filter of my shower drainage supposed to be cleaned out that many times a week? Or is it just my long beard contributing to the blockage? I’m definitely not young anymore, and indeed there are other parts of my body that perk up uncomfortably to remind me that my time to leave this life is always sooner than I think. As the Tibetan saying goes, “Old age is not guaranteed, but your next life is!”

Contemplating my own death repeatedly proves itself to be a powerful way to be returned to my priorities. It boils down to one question: Given my definite demise, what am I going to do with this unique and precious day? There is no guarantee I will see this day to its end, no promise that I will lay this body back down in bed the same way it arose this morning. I believe that when I finally do face death, what will truly help me is the clarity of my conscience and the quality of my awareness. These are not things that I can cultivate in a short time span, but are a result of the positive momentum I add to every day of my life. What shall I do to meet death without fear and regret? Will I be surprised and feel that I’ve been cheated by life, or is there some way to approach that transition with positive anticipation? Perhaps, I hope, I will settle down with a sense of peace, even celebration, knowing that I treated others well and worked every day to uproot my very own mental afflictions—afflictions that cause pain to myself, other human beings, and animals, not to mention the environment I inhabit.

In order to be touched as I am, to make genuine change in my priorities and attitudes, I need to let the reality of death and impermanence actually be real for me. I can meet that reality through genuine insight, because death is always happening, and for such insight, that takes tending. One of my long-held practices is one where when I say goodbye to someone, especially when it will be for more than a couple of weeks, I take in all detail possible of that moment, like taking a mental photograph with all my senses, and secretly bow to the possibility that this might be the last time I see this person alive. This not only brings me closer to the reality of death, but also to the delicateness and preciousness of life and my relations.

Humor

“God and I have become like two giant fat people living in a tiny boat. We keep bumping into each other and laughing.”

This is my favorite poem of the great Persian Sufi poet and mystic Hafiz.

How do I know when I am bumping up against something sacred? Sometimes in the middle of a meditation session I burst into laughter. The slightest something breaks the rigid symmetry of my serious attitudes and there I am, cracking up all on my own in my meditation box. Tears also come regularly, spontaneously, secretly showing the world the gratitude I have for my life, for all the kindness I’ve received. One could dryly say that these are only moments of catharsis, just the nervous system letting off some pressure. I don’t think so.

Sometimes I am rubbing up against something holy and don’t regard it as such. All I feel is agitation and impatience, as if I’m being dragged, unable to find any satisfying reason why I’m so frustrated. This may go on for hours, even days. Then something suddenly becomes clear—like finally getting the message, whether through a harsh truth or gentle advice—and I see that I was indeed so close to something important to me: an insight, a moment with the divine, a reconciliation waiting to happen, a recognition of something primordially pure—but because of my own limiting conceptions and addiction to my beliefs, I buffered myself from them. In hindsight, I see it was just fat old God bumping into me, and I was refusing to laugh.

Now, coming to motivation: what’s the point of it all? Why am I in this retreat? Why bother with all the hardship and spending so much time and effort cultivating the mind to this extent?

What is the Point? Compassion

I quote my beloved Jewish World War II heroine, Etty Hillesum, who speaks it all for me (these are two quotes put together):

“It is the only thing we can do. Each of us must turn inward and destroy in himself all that he thinks he ought to destroy in others. And remember that every atom of hate that we add to this world makes it still more inhospitable.”

“Ultimately, we have just one moral duty: to reclaim large areas of peace in ourselves, more and more peace, and to reflect it towards others. And the more peace there is in us, the more peace there will be in our troubled world.”

It’s been well warned for thousands of years in India and Tibet that it’s awfully dangerous to get caught up in one’s experience of the natural sense of well-being, power, and peace that arise due to sustained meditative practices like shamatha. There is the danger of isolating oneself in an enjoyable bubble, far from the harsh realities of the wider world. But no one is an island, and I believe the great practitioners of old Asia, like all great contemplatives, knew this better than most.

The point is to gain insight, to know how things really work. Shamatha makes the mind serviceable, refining the attention and senses so we can actually perceive and know definitively what is happening in reality at whatever level. And reality, ultimately, is said to be one of profound interconnectedness. It’s one thing to have intellectual understanding of how intricately intertwined our lives and sources of well-being are, and much virtue derives from that deep, conceptual insight. But já é outra loiça (it’s a whole other dish) to have direct, unmediated experience of reality firsthand, beyond any addictive ideation and even our psychological matrix. And that experience, as has been told, gives rise to spontaneous, undeniable, heartfelt compassion for all life. It’s said that it’s as if each person becomes your only dear child. Can you imagine that?

Besides death, I contemplate compassion every day. Until I reach that state of spontaneously arisen love and compassion that undoubtedly leads to meaningful action, I will do what I can to cultivate my mind and heart to be able to, as much as I authentically can in each moment, hold all of life’s complexities and the mess we humans have gotten this planet and ourselves in. To again quote my dear Etty Hillesum: “We should be willing to act as a balm for all wounds.”

I’m in this shamatha retreat to train my attention and love in order to offer relevant help to individuals and our larger situations. I often remind myself that the word “attention” is related closely to the word “tend,” the same word we use when we take care of the injured and sick. I won’t hold back from acting just because I don’t have ultimate wisdom, nor will I stay in a cave seeking isolated perfection for eternity, but I am seeking a meaningful, dynamic balance between these two activities. After all, it is within us and among people—including animals and all forms of life—where the word “wisdom” even begins to have any relevant meaning. And in our troubled times, we desperately need wisdom.

When I am in need of inspiration to cultivate the two wings of wisdom and compassion, I need look no further than His Holiness the Dalai Lama. This is a person who lost his country, who has witnessed the decimation of thousands of years of Tibetan cultural heritage, the destruction of thousands of monasteries and sacred places, his people imprisoned in work camps, dehumanized, starved, tortured, with many killed publicly or gone missing. When asked how he can remain so happy and engaged despite all that has happened, and is still happening, with very little hope on the horizon for Tibet and its people, he answered with one word: wisdom. He has never shown hatred or sworn revenge on the Chinese people or politics, despite his unending resolve and absolute stance for independence and fairness for his country. In fact, he has only shown great kindness and compassion to the Chinese, as if he too were their patron.

Landing in Gratitude

It was a conversation with some friends who are parents that encouraged me to go deeper into this kind of training. Each told me that when they were in their teens or twenties, they clearly knew that being a parent was their path. For many years I thought I was broken, as if my parent-gene was lagging sluggishly behind, even though being an educator of youngsters called me early on in life. By witnessing my friends’ enthusiasm and certainty of that wish, I recognized that I too had that kind of enthusiasm and certainty when I was younger, but it wasn’t for becoming a biological father. Rather, I had a primal urge for deep and sustained spiritual (though I don’t like to use that word so often) training.

As a young man, sex and parties were interesting, but only to a certain extent (though much later on women became an essential part of my path for learning unconditional love and the sacred). From University parties I often left early and alone, to wander home drunk with a sense of yearning, concerned for the depressed people I drank with, and looking at the stars and contemplating the sacred. Ha! But alas, there was no room for that contemplation in my wider culture, nor in the future of any career—no role models of professional contemplatives as the many ancient cultures had, no context for those who feel the call to go into solitude to gain wisdom and share it with the commons where it belongs. So instead, I continued to study Physics. I tried to get some insight into reality through that brilliant but limiting discipline before stumbling forward into young adult life, trying to seek a meaningful path. I am so grateful to have found the work and teachings of Dr. B. Alan Wallace and Dr. Eva Natanya, who have given voice to this calling I’ve felt since childhood, and the space they’ve created for us to truly fathom the mind for the benefit of all beings.

From the depths of my heart I thank not only my close friends and family, but for everyone who has contributed to the Retreatant Support Fund or otherwise supported me, making this retreat possible. I couldn’t be here without your generosity and care. Making lots of money has never been my forte, but fortunately making friends with virtuous and kind people has! I hope I can one day return your kindness.

With sincere gratitude,

Benjamin

January 2025

“We can make our minds so like still water that beings gather about us that they may see, it may be, their own images, and so live for a moment with a clearer, perhaps even with a fiercer life because of our quiet.”

~William Butler Yeats, The Celtic Twilight

Griffin Cunningham shares how volunteers came together to create the CCR's newest educational offering.

Dear CCR community,