RE-ENVISIONING THE GOOD LIFE

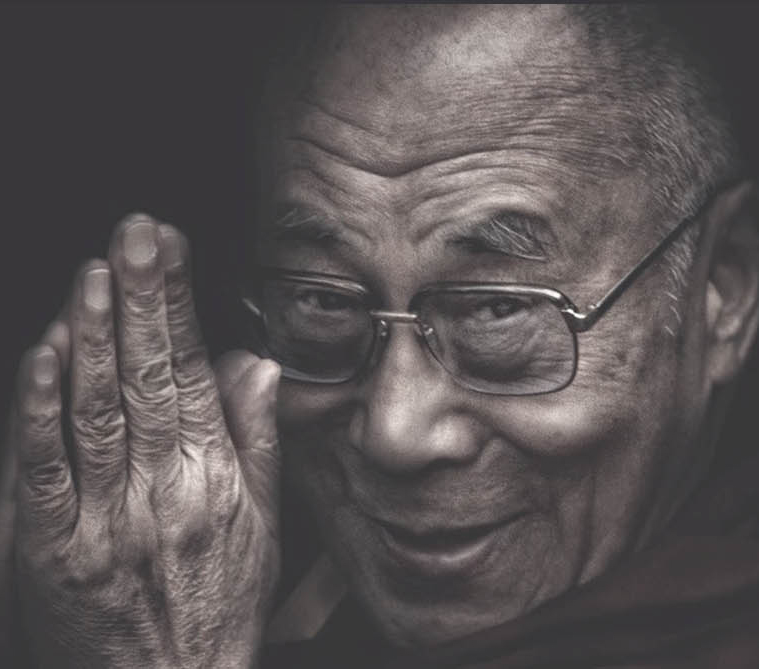

I believe that the very purpose of our life is to seek happiness. Whether one believes in religion or not, whether one believes in this religion or that religion, we all are seeking something better in life. So, I think, the very motion of our life is towards happiness.

— His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Genuine well-being

The key to the good life is the cultivation of genuine well-being, what the ancient Greeks called “eudaimonia.” This is a sense of flourishing derived from an ethical way of life, from mental balance, and from wisdom. It is a joy that comes from within, without relying upon pleasant stimuli.

On the other hand, “hedonia,” or mundane pleasure, refers to the joys that arise in response to pleasant stimuli, be they sensory or mental. The pleasure arises in response to the stimulus, for as long as it lasts, but fades when the stimulus is no longer there.

Hedonia is crucial for our survival.

Eudaimonia is crucial for our flourishing.

There are indeed five elements of hedonic well-being that are crucial: food, clothing, shelter, medical care, and education. These are fundamental requisites for living in our world, and the happiness we experience on their basis is hedonic.

Yet, as Thomas Aquinas stated (in his Commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics): “the whole of political life seems to be ordered with a view to attaining the happiness of contemplation.”

The term “political” in this quotation refers to the structures that provide our basic needs for survival, including government, business, education, etc. All the hedonic pleasures that sustain our life, according to Aquinas, have as their objective the higher purpose of nurturing a contemplative life, a life devoted to finding lasting, enduring well-being that is not dependent on external stimuli or various forms of external validation, such as wealth, power, fame, and status.

The nature of hedonic pleasure is that we always want more, for it never satisfies.

So, how can 7.8 billion people on the planet continue on our current trajectory of ever-increasing acquisition and consumption without depleting the ecosphere to the point that human civilization is doomed? The natural resources of the earth are finite, and the human population is growing, so the non-renewable resources of our world are vanishing swiftly, as is the wildlife with whom we share our planet. Gandhi is famously quoted as saying: “In the world there is enough for everyone’s need, but not for everyone’s greed.”

The pursuit of hedonic pleasure by way of the acquisition of wealth, power, and status is by nature competitive. The more one person, family, community, society, or nation has, the less others have. Inequalities inevitably arise, but the inequality of wealth distribution in modern civilization is unprecedented and unsustainable. Conflicts are bound to arise between the “haves” and the “have-nots,” and the cycle of violence will continue as humanity perpetuates its own misery. This has been true throughout human history, but the juggernaut of materialism, hedonism, and consumerism that dominates human civilization in the twenty-first century imperils as never before the ecosystem on which our survival depends.

Our survival and flourishing depends on this fundamental shift in our priorities and our vision of the good life.

During the twentieth century, scientific knowledge of the objective world increased exponentially, to such an extent that it has been said that we learned more about reality in the twentieth century than we did in all preceding centuries combined. Advances in technology were just as dramatic, improving the health and longevity of billions of people and enhancing the quality of life for many, especially those living in so-called “developed” countries. But the twentieth century also witnessed the bloodiest wars in history, unprecedented degradation of the environment, and the extinction of much of the wildlife on earth and in the oceans. It was the most destructive century for the planet in the history of the human species, surpassing even the massive devastation caused by the giant meteor that hit the earth 65 million years ago. Just since 1970, we have wiped out 60% of the mammals, birds, fish and reptiles on the planet. Scientists show us that the rate of this destruction is only increasing during this twenty-first century, undermining the balance of the ecosphere as a whole and human civilization in particular. We have become our own worst enemy.

While science and technology have greatly contributed to our material well-being, they have not helped us become more ethical—that is, more nonviolent and more benevolent. They have not led to a decrease in our greed, hatred, stupidity, or arrogance, nor have they enhanced the mental health and genuine well-being of humanity. Scientists have shed a bright light on innumerable aspects of the objective, physical world, but have, for the most part, left us in the dark regarding the subjective world of the mind. The origins and nature of the mind and its relation to the body remain as much a mystery now as they were when the scientific study of the mind began in the late nineteenth century. Likewise, the inner causes of mental distress remain largely unknown as mental diseases continue to be treated primarily with psychopharmaceutical drugs, which suppress the symptoms of mental illness, without actually curing a single one.

Moreover, the nature of consciousness and its role in the universe remain a mystery to science, largely due to the ideological and methodological constraints of materialistic reductionism. Finally, while the nature and inner causes of genuine well-being were deeply explored by the ancient Greek philosophers and the sages of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, their discoveries remain largely ignored in the modern mental healthcare system that developed within Eurocentric cultures.

With the growing human population and accelerated exhaustion of the world’s natural resources, humanity is currently on a course of self-destruction. If we continue to equate “the good life” with the hedonic pleasures acquired by way of wealth, power, and status, we are doomed. To meet this current crisis, humanity must learn to place a higher priority on the cultivation of eudaimonia than on the pursuit of hedonia. It’s that simple.

Genuine well-being can be realized.

While the pursuit of hedonia is by nature competitive, the cultivation of eudaimonia is collaborative. While the experience of hedonia is invariably transient and eventually unsatisfying, the cultivation of eudaimonia is sustainable and ultimately fulfilling.

The external resources of our planet are limited, while the inner resources of the human mind are fathomless.

The great contemplative traditions of the world, both Eastern and Western, hold our greatest treasures of wisdom regarding the nature and potentials of consciousness and the ways to cultivate genuine well-being.

They highlight three specific domains in which genuine well-being can be realized:

a) living an ethical way of life—which leads to social and environmental flourishing,

b) cultivating exceptional mental balance—which leads to psychological flourishing, and

c) generating wisdom—which leads to spiritual flourishing.

By leading an ethical way of life based on the fundamental principles of nonviolence and benevolence, we can flourish together in human societies, with the other species with whom we share this planet, and with the natural environment as a whole.

By healing the inner afflictions that lead to mental distress, by cultivating various aspects of mental balance—including conative, ethical, attentional, cognitive, emotional, and spiritual balance—and by exploring the inner resources of the mind—including loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and impartiality—we may experience unprecedented psychological flourishing.

And finally, by cultivating insight into the depths of human nature, our own identity, and our relation to reality as a whole, we may rise to a level of spiritual flourishing that fulfills our deepest longing.